Hard Times at Douglass High presents a school in need of being torn down and built anew.

If matters were fast and friendly at Ridgemont, they are far harder and frantic at Douglass. The great irony of Douglass is that in times where separate but equal was the standard, it was the exception; and when times are no longer separate but equal, it is – as the film declares – “separate and not equal.” While the film is chockful of illustrations proving this point, there are none more potent than that of the principal, who says that of all 10th graders, three were at grade level in reading. Most were at the fourth grade level. This is a shocking fact, one that is unfortunately common to many urban schools. Have matters improved at all in the past decade, particularly since the implementation of No Child Left Behind? According to a white male administrator, the problem is one he and everyone else is aware of – and yet, like an overexposed wound, it will be left to fester.

The full title of the documentary alludes to its accusational tone: Hard Times at Douglass High: A No Child Left Behind Report Card. While issues have existed at Douglass since its student population has become almost exclusively black and poor, it does not seem as though No Child Left Behind has helped. If anything, it has compounded the problem. As one of the teachers says (I do wonder if his candid comments affected his job status, or he presumed himself safe because he is a debate coach and of Hispanic descent), it is not in the state’s best interest to take over a school. Nor is it realistic to expect all students to 100 percent proficient by 2014. By setting unrealistic expectations and delivering punchless ultimatums, No Child Left Behind actually enforces the status quo. Students continue to graduate and be college bound at suburban schools and continue to dropout and resort to street life at urban schools such as Douglass. At a school in which the dropout rate is nearing 60 percent, it is clear that there is little cause for ovation. The tagline for keeping students enrolled seems to be twofold: graduating and getting a job (though at parent/teacher conferences, the prospect of college is mentioned with the same degree of excitement as a pipedream). For the purposes of this review, I would like to focus on the perceived effectiveness of non-minority teachers as educators (and disciplinarians) vs. their minority colleagues.

Principal Isabelle Grant, who happens herself to be a Douglass graduate, has a firm grasp on the behaviors of the male black students sent to her for disciplinary issues. Is it because she reminds many of them of their own grandmothers (a matriarchal figure, perhaps?), or is it something else? While a disciplinarian when necessary (though it is important to note that students are occasionally shown reverting to former wrongdoing once her presence is gone), she is for large part the students’ and school’s greatest ally. Her boasts of the parental interest in PTA is almost comical. Early in the documentary, some grafitti is shown that condemns the act of snitching (telling authorities what you know about a crime at the expense of someone else). For Grant to say a negative word about Douglass is the same as snitching – to foresake the promise is to foresake her role in her students’ lives. Building on what we as a class viewed earlier in the semester, Grant begins the day by speaking three words of encouragement: pride, dignity and excellence. Is echoing such words day after day a useful tool to build self-esteem? Or is it really a cause for laughter among students? Grant seems more than eager to cater to what her students want if it means keeping them enrolled at Douglass. She knows that some of her students are borderline dropouts on the basis of being stranded at a grade level that is sometimes three years behind their ages. If they promise to come everyday and be cooperative, she will place them on the “fast track,” which will allow them to graduate with their class. I don’t see how it’s possible for a student to close such an educational gap in mere months. In other words, Grant may be bolstering her school’s graduation rate via such practices, but she is guilty of awarding diplomas to students unable to read at their age level. If a student cannot read, what good is a diploma against the call of the streets?

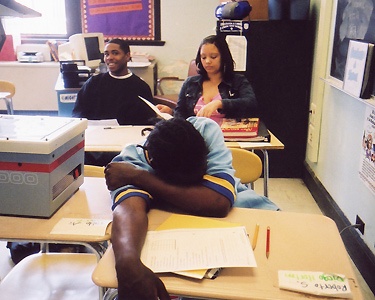

Then there is the white male English teacher, who, upon first glance, is like a white log lost adrift a fast-moving current of black students. His countdown method to getting the classroom’s attention is elementary – and hardly effective. While he is speaking, a few of the students continue talking in a whisper. Instead of relating student experience directly to literature, the teacher allows students to amplify the negativism they encounter every day. Students talk about people they know who are pregnant or were shot over a drug deal gone bad. One student, a black female, relates how a person with a criminal record has a history that will remain with them forever and, therefore, could never rightfully mentor another person: that a discordant act is like a never-healing black eye. By reinforcing the environment in which they live (and not showing any willingness to share some of his life experiences), how is this teacher reaching out to his students? It is almost as if he’s perpetrating the notion of education as myth in the urban setting: that his job is to be a ringleader that guides the lions and lionesses through a flaming hoop. It is clear that this white male English teacher is out of his element: any relationship with his students is non-existent. Perhaps if he knew his students better and sought to learn from what they’re telling him (he appears to be dumb to their pleas), he could expect a parent to visit him during parent/teacher conferences. (I resented his watch-watching, damn-if-they-do-come behavior.) While I understand some of the blame must fall on the parents themselves (though many of them work jobs that occupy evening hours), I saw nothing in the white male English teacher’s repertoire that made me believe he cared to understand his students. And his environs were as devoid of inspiration as his approach to teaching.

On the other hand, there is Douglass’ recording arts and media production class, a hugely popular course that strives to teach students how to produce their own music and videos. While the English course mentioned above seems disconnected from synthesizing student experience with newly learned material, the recording arts and media production class appears promising. Why? Because it embraces black culture and it is taught by an instructor who is black and not afraid to be creative around her students. While it is no doubt important to consider student interest when designing curriculum (and for a teacher to be openly creative), I wonder if a course such as this one has gone too far. How can students benefit from this course? By being provided a platform to rap about deviant subjects? I don’t foresee how, in the long run, a course such as this one helps students any more than one founded in basketball or football. But whereas dreams of being a professional athlete are often dashed early, the dreams of a wannabe rap artist or producer die hard.

In conclusion, Hard Times at Douglass High presents a school in need of being torn down and built anew. In a way, it seems that all students are learning is a society-as-oppressor philosophy (even the basketball coach does not lay a loss at his own feet or his players, concluding that the team was “fucked by the officiating”). The students of Douglass High, most all of whom are black, are ignorant to the ideals of the Harlem Renaissance or Civil Rights Movement. By having administrators and educators remind them of who they are and where they come from (even the Teachers for America-cuffed Spanish teacher seems to be more annoyed than genuinely compassionate toward her students), the 40 percent of students who do graduate from Douglass High have little hope for college or gainful employment. After all, the world they come from is harsh and, if their schooling is any indication, they will never shed its ails.