We’d love to have more commercial,” O’Renick said. “And I think the Sugarland Center is the winning ticket.”

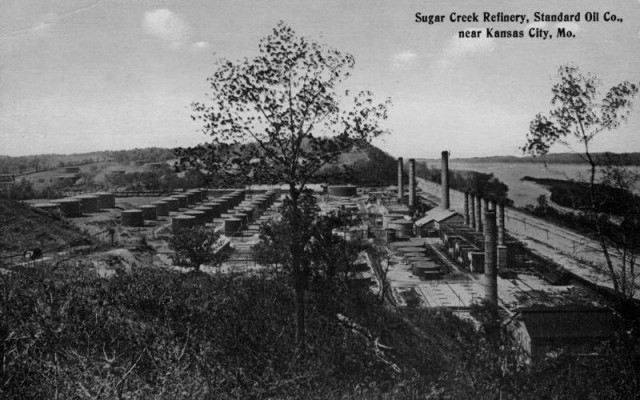

ack O’Renick remembers the year Sugar Creek stood still.

It was 1982, and the city’s chief source of revenue and job security was dead.

The BP/Amoco refinery had closed after nearly 80 years of operation.

“The city learned a hard lesson that year,” said O’Renick, who served as the city’s mayor from 1980 to 1992. “You can’t put all your eggs in one basket like that and not expect it to hurt a bit.”

O’Renick said the city, though brought to its knees, was able to regain its footing by the time he left office.

He attributes this to the 100 businesses in the city as well as the approval of a small sales tax issue. The city also cut expenditures to a minimum.

“We got the boat righted again, but it hasn’t necessarily been smooth sailing since,” O’Renick said.

In the past couple of decades, businesses in Sugar Creek have fallen like the leaves in autumn – only, come spring, there’s no regrowth.

“We’d love to have more commercial,” O’Renick said. “And I think the Sugarland Center is the winning ticket.”

Sugarland Center, a 225,000 square-foot retail center, will include a winery, multiple restaurants, a 45,000 square-foot supermarket – which will be operated by Associated Wholesale Grocers, whose store concepts include Price Chopper and Hen House – and an undetermined 130,000 square-foot anchor (Jeff Peterson, the developer of the project, said the space could be filled by Target or a large home improvement store). It will be located along the northwest corner of U.S. 24 and Sterling Avenue and would occupy land where 57 homes and 15 businesses currently sit.

Eight months ago, a planner hired by the city found the area blighted – citing a slew of infrastructure problems and the substandard condition of many homes in the area – thereby creating a tax increment financing district; in late August, an ordinance was passed granting the city authority to use eminent domain if negotiations with homeowners fail. So far, the city has managed to purchase 30 of the 33 properties in phase I of the project, which will include the construction of the supermarket.

All three of the remaining homeowners have refused to accept the city’s offers for their properties, citing everything from unreasonable compensation to health concerns to family legacy.

O’Renick said he empathizes with their plight.

“I fully understand how difficult it can be for somebody to give up their home, particularly if their health isn’t well,” O’Renick said. “I just want those who are left to stop and think about what good this could bring not only for the city of Sugar Creek but the whole area, including northwest Independence and Englewood.”

Although the Apple Market is close by, O’Renick said the closest true supermarket is a 20-mile round-trip away; a considerable distance for Sugar Creek’s elder community.

“If we can make Sugar Creek a place to shop, I think it would make life a lot easier for those whose health and age plays a factor in their ability to drive,” O’Renick said.

He said he’s hoping the anchor tenant for phase II of the project is a home improvement store.

“With it being 10 miles or so to Home Depot and back, I can imagine a lot of tasks around the home get neglected in Sugar Creek,” O’Renick said. “A new home improvement store sure would fix that.”

When O’Renick was mayor, he prided himself in not seeking the assistance of state or federal agencies to recover from the loss of the refinery.

As a fourth class city, he said Sugar Creek doesn’t get the tax boost that bolsters bigger cities.

“In larger cities, funds from community development block grants are a given every year, whether they’ve applied for them or not,” O’Renick said. “We’ve had block grants before, but it’s not that common.”

According to O’Renick, if a city such as Sugar Creek cannot get community development block grants, it can use TIF dollars to stimulate the redevelopment of an area. A TIF uses a portion of local property and sales taxes to assist funding a redevelopment. In Missouri, an area is not eligible for TIF unless it is classified as having blight.

O’Renick concurs with the city’s strategy of seeking TIF to bring about positive change.

“We’re a small, close-knit community that does things for itself,” said O’Renick, a third generation Sugar Creek resident. “This could be the catalyst this city needs to really blast off.”