Now why go way out there? We’ve got a hustling town right here; big trade with Mexico; lots of border money; thousands of outfits stock up here, and there is always plenty of work. You’ll never find a better place to settle.”

t had been many years since I’d last seen John McGee, a childhood friend of my dad’s. My memories were of a tall, slender man who was leisurely dressed during his summertime visit to my parents’ house at Lake Tapawingo so long ago.

What I knew about John McGee then was that he was mild-mannered, someone who was at once a patient listener and engaging conversationalist. I didn’t know that he was an executive officer at Commerce Bank nor that his forebears were the ones for whom McGee Street was named. In autumn of last year, my dad and I met McGee at City Diner, located at 3rd Street and McGee in the River Market District of Kansas City. Besides an opportunity for McGee and my dad to catch up, the meeting had a purpose: the idea of a renovated downtown is a source of excitement for both my dad and I, and we wanted to hear the opinion of a McGee descendent.

My dad and I arrived at City Diner five minutes before noon; John McGee ambled through the front door at precisely noon. John McGee’s face had a look of concern. “I haven’t kept you all waiting, have I?” John McGee said. My dad assured him he had not. The two spoke for a moment about old friends and old memories, then my dad got to the point: “John, I like what’s happening downtown.” John McGee’s follow-up was no less optimistic, if tempered more at future promise than complacency in the present. “It’s a beginning; a good beginning,” said John McGee, his voice trailing to a whisper. “You know, my office at Commerce Bank was once in the middle of my great-great grandfather’s farm.” My dad asked him what kind of outlook his great-great grandfather James Hyatt McGee had for Kansas City. “I think he probably envisioned a small river town, something peaceful like Weston or Hannibal.” What about James Hyatt McGee’s estranged son Milton McGee? “My great uncle had grand ideas – like that Grand Street out front.” When we finished eating and my dad and I gave him a farewell handshake, John McGee left us with a statement: “You should see the Steamboat Arabia Museum before you go. It has a lot to do with the period we’ve been talking about.” As we looked west across Grand Street, we saw a building housed in glass and in big, bold letters: Treasures of the Steamboat Arabia. My dad and I looked at one another and nodded our heads. We were on to the Steamboat Arabia Museum.

teamboat Arabia was discovered beneath 30 feet of mud in July 1987 in a Kansas cornfield. A snag at Quindaro Bend on the Missouri River downed the side-wheeler Sept. 5, 1856. The only casualty was a mule tethered to the vessel’s haul. The tour guide – a woman whose passion for retelling history rivaled the inner-ambition of the pioneers venturing west during the Arabia’s demise – told us that much of the boat’s contents were preserved because the snag struck so ferociously the vessel sunk in minutes. The museum is a haven for the artistic and well constructed: some of the objects on display include Italian-imported chinaware, India-rubber overshoes and enough ironworks for a fleet of blacksmiths. But perhaps the museum’s greatest strength is its testament to a bygone era, to the hordes of men, women and children who saw the American Dream in the unknowns of the frontier.

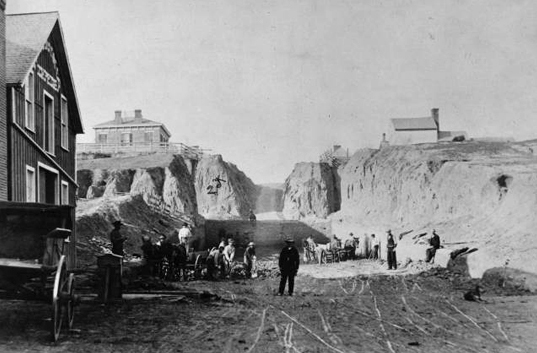

Afterward, my dad and I parted ways – my dad homeward, myself to the market to buy a bushel of area-grown Jonathan apples. But I wasn’t ready to go home. No, I wanted to learn more. I remembered reading about the multi-million dollar improvements to the downtown Kansas City Public Library. What interested me most about the renovations was the Missouri Valley Room, a refuge for enthusiasts of all things history: the fur trade, Indians, religious groups, explorers and families and figures of local relevance – such as the McGees. In a large room that was quaintly furnished, I gleaned a bevy of articles, renderings and photographs that depict the forging of a frontier town and the aspiration for something greater. In one image, dated 1868, a man clothed in black stands at the center of a rustic scene in which Walnut Street has been carved out of bluffs hundreds of feet high. The photograph made me realize just how ludicrous Kansas City’s formation may have seemed to some: why invest such manpower in a city that must be whittled from limestone?

From the Kansas City Public Library, I drove west to the Quality Hill neighborhood, stopping off at a 200-foot overlook on the northern end of Case Park. The view of the Missouri River is the same as Lewis and Clark witnessed on their return trip from the Pacific Ocean Sept. 15, 1806. Peer west at the overlook, and you’ll find the water-borne rationale for Kansas City. Like Missouri’s other great city, St. Louis, Kansas City is nestled at the confluence of two rivers – the Missouri and the Kaw, a 170-mile river that empties six tributaries including the Big Blue of Nebraska and the aptly named Beaver Creek of Colorado. But wasn’t merely the merging of the Missouri and Kaw rivers that made Kansas City. It was a natural rock levee (three city blocks in length) located just north of modern-day Main Street that made the area a perfect spot to park a boat, hold a rendezvous, talk, trade and do business.

efore the land knew the name McGee or McCoy (Westport’s founder), it was under the thumb of Francois Chouteau, the young grandson of St. Louis’ founder, Pierre Laclede. In 1821, Chouteau opened a trading post on the southern bank of the Missouri River north of what today is Troost Avenue. The Chouteaus were a French-Creole family made rich by monopolizing the fur trade and forging a partnership with John Aster’s New York-based American Fur Company. For much of the first quarter of the 19th century, Europe’s hot item was the beaver felt hat and, by establishing an outpost at the confluence of two large rivers so early into Missouri’s statehood, the Chouteaus hoped to squelch all competition. In 1826, flooding caused the trading post to be relocated to higher ground near today’s ASB Bridge. Shortly thereafter, a small French-Creole village was established. Consisting of two-dozen families, it was a community of trappers, traders and mountain men – many of whom had married Indian women and conceived half-breed children. In addition to homes, there was a tavern, a church and a schoolhouse. (Nothing remains of the community today.) The Chouteau foothold would not last, however. Soon they were outnumbered by pioneers of Anglo-Saxon stock and had no choice but to push toward the Rocky Mountains. The knockout to the Chouteau legacy occurred in 1835 when silk hats replaced beaver as the more popular European fashion.

In that same year, the bust of the beaver trade ushered in the boom of Kansas City’s second developmental phase when the town of Westport was established four miles south of the levee, which would be coined Westport Landing – a regional hotspot for steamboats to load and unload goods. Westport wasn’t meant for settlement but rather, like the name implies, it was a port west: a stopover of liveries, eateries and saloons on the Santa Fe Trail. It also serviced reservation Indians looking to spend their government annuities. John McCoy was the man most responsible for Westport’s founding. While McCoy foresaw the land at the junction of the Kaw and Missouri rivers as a launching point for westward expansion, James Hyatt McGee foresaw a place people could call home.

hen Congress declared Missouri a state in 1820, it opened the floodgates to a torrent of white settlers seeking land on which they could act as farmer – and prospector. Many of these newcomers were veterans of the War of 1812 who, for their service, were awarded land from the federal government. James McGee – a native of Shelby County, Kentucky – had been promoted to captain in the war and was thereby privy to land grants. James McGee migrated to Clay County in 1827 on account of his brother-in-law Solomon Fry, who arranged a government position for James McGee and his wife Eleanor that involved grinding flour for reservation Indians.

A year later, the McGees crossed the Missouri River, purchasing a squatter’s claim of 320 acres. In 1833, the McGees tripled their domain, making one sizeable land grab after another. According to the historian Mildred C. Cox, James McGee was “one of the land hungriest men in the country.” The McGee farm occupied an area stretching north to Ninth Street, south to 27th Street; its eastern edge grazed Troost Avenue and on the west it extended to Summit Street. The McGees lived in a log cabin at 20th and Central before moving to a bigger home just west of Baltimore and 20th. The McGees’ business investments were limited to a distillery and a flour mill. The biggest interest for James and Eleanor McGee lay in the land next to the levee, a rock formation James McGee noticed during the brief time he operated a ferry service.

The landing belonged to the Prudhomme estate, which sat on 256 acres, including virtually all of today’s river market district. As happenstance would have it, Gabriel Prudhomme, the estate’s French Creole owner, was killed in a bar brawl in 1831 leaving behind a pregnant wife and six children. Soon afterward, James McGee was appointed guardian of the heirs, who were ordered by the court to sell the land because it could not be divided justly. The initial auction of the land was held in July 1838 with James McGee its crier. Abraham Fonda had the winning bid of $1,800, which was later rejected due to a small turnout. A second sale was scheduled in November. This time it was official: Fourteen individuals, including McCoy and the legendary mountain man Bill Sublette, could now lay claim to the land, which was bought for $4,220 and became the original townsite company of the town of Kansas. Another of the buyers was Fry McGee, James and Eleanor’s dutiful son, who proposed the tract’s lots be sold on credit of six or 12 months; the lots went quickly and soon the levee had the appearance of a world-class seaport. By late 1838, James McGee was ailing and knew he didn’t have much longer to live. But Fry McGee would not be the one to manage the family’s business interests, living for a spell in Oregon Territory before operating a pro-slavery tavern on the Santa Fe Trail following Kansas’ admission as a territory in 1854. When James McGee died in May 1840, his wife did not follow. Eleanor McGee survived her husband by a half century, overseeing all matters of business. She kept the family’s holdings intact and truly was Kansas City’s matriarch.

One year after James McGee’s death marked the homecoming of an errant son, Milton McGee, who left the family to fight in the Seminole wars of Florida after blackening his father’s eye at 16 (according to Milton McGee’s recollection, anyway). But Milton McGee’s stay was temporary; a few years later, after admitting his failures as a farmer, he departed to California in whose mines he sought instant riches. And it was riches he found, returning to Kansas City on a horse anchored by saddlebags brimming with gold.

He would use the money to buy 240 acres of farmland south of 12th Street between Main and Holmes. The acreage, to be known as McGee’s Addition, was a distance from the riverfront and difficult to access; its route was littered with near impassable gullies and bluffs. Milton McGee saw Kansas City not as a sleepy little hamlet like his father but a bustling metropolis. And he was to be its developer. But he needed an artery that could pump the blood of commerce. Milton McGee would name it Grand Avenue, a street twice – if not thrice – as wide as any other. He promptly built a fancy hotel at Grand Avenue and 16th Street followed by a row of two-story brick buildings at Grand and 13th Street, then the middle of a cornfield. Milton McGee lived by the axiom that a lot wasn’t worth selling unless the buyer intended to build on it. In early 1857, McGee’s Addition was vacant save three small buildings set aside for McGee’s house. One year later, there were 117 buildings along each side of Grand Avenue rowed as far as the horizon. The population on the tract now numbered 700 and featured countless grocers, butchers, lumber dealers and repairmen.

ilton McGee, whose immaculate dress and well-trimmed handlebar moustache were unmistakable, was known to greet passers-by at the levee, promoting a place to settle rather than merely a place to outfit. Annie Taylor was 10 years old when she and her family arrived at Westport Landing. Awaiting them was a man riding “the most beautiful horse I ever saw,” Taylor said. Milton McGee approached Taylor’s father directly, asking him of his plans. He had none, only to follow a trail west to unchartered lands. Milton McGee gave a sales pitch: “Now why go way out there? We’ve got a hustling town right here; big trade with Mexico; lots of border money; thousands of outfits stock up here, and there is always plenty of work. You’ll never find a better place to settle.” To sugarcoat the proposal, Milton McGee sold Taylor’s father three lots, located a tent for them and sent a wagon to collect their luggage.

Milton McGee – a man about town who served as mayor, state representative and state senator – never ceased his role as Kansas City’s great promoter. He built a Metropolitan Hall for town meetings and a gargantuan Fourth of July ball he himself hosted, bought and renovated the Farmers Hotel, established a hook and ladder company and ran a horse-car trolley between Westport and Kansas City. And, as the rivers and trails yielded to the coming of the railroad, Milton McGee assured Kansas City’s part as transportation Mecca. He died in February 1873 in his home, a mansion befitting a showman: its entrance gate was made from the lower jawbones of a whale, and its grounds boasted a five-acre petting zoo that included a brown bear, a dozen deer and two bald eagles.

But Milton McGee’s proudest contribution remained Grand Avenue, which he hoped to be a commercial pipeline far after his dying breath. Indeed for decades downtown Kansas City was a vital place – then it wasn’t. Westport, the town Kansas City unseated, was the premier hot spot for fun. Recently, however, the area on and approximate to Grand Avenue has been given new life in the form of businesses, restaurants and attractions. It’s as if Milton McGee’s ghost has arisen.

returned to downtown Kansas City in late January to observe its Saturday nightlife. Temperatures hovered near the freezing mark as the full moon transformed Grand Avenue into a great glittering current. Grand Avenue might as well have been an arm of the Missouri River, a swell of energy pushing north to south through Kansas City’s heart. Even on a night in mid-winter, the Power & Light District was a hive of activity. At Willie’s, there was the hurrahs and boo-hoos of a closely contested basketball game; at Raglan Road Irish Pub, there was the shuffle of feet to the beat of an Irish jig; at Howl at the Moon, a jazzy number sparked swoons of courtship. But across Grand Avenue was the grandest marvel of them all – the Sprint Center, a shimmering crystal in the night. Beneath an electronic display previewing upcoming concerts was a man whose face was forested by a dense beard. His eyes locked on mine from afar. “How are you tonight?” I asked. “I’m well,” he said, walking north along Grand Avenue, his boots striking the sidewalk pavement like a chisel. His parting words: “All is well.”