Development is inevitable,” said Wendy Shay, historic preservation manager for the city of Independence. “The only way to defend against it is with foresight.”

he Battle of the Little Blue was once regarded as nothing more than a prologue to the bigger Battle of Westport, the tragic end of Major General Sterling Price’s hope of reclaiming Missouri for the Confederacy.

While the battle out west was no doubt greater in terms of troops, it was a daylong series of skirmishes along a seven-and-a-half-mile strip of what is now eastern Independence that carried with it a plotline rife in military bravura and bravado as well as a brand of combat so fierce that traces of its wrath still stain floorboards at the Lawson Moore Home, also known as Shelby’s Hospital.

Today the area on which the Battle of the Little Blue unfolded remains immaculately preserved, a vista as handsome as it is haunting with its steep rock faces and hollows. A fury, however, is coming; not one of destruction but, rather, construction as a four-lane, divided roadway knifing through the southern part of the property is projected to bring with it 7,000 new homes, 20,000 new residents and 5,000 new jobs. Its 2010 completion date isn’t the chief concern. Far more daunting is the South Riverfront Expressway that will connect Sterling Avenue to where the parkway ends at U.S. 24. According to the Mid-America Regional Council, the organization planning the 24-mile Missouri River Corridor project including both roadways, the western edge of the battlefield marks an ideal route.

“Just imagine it,” says Mike Calvert, president of the Civil War Round Table of Western Missouri. His hand sweeps over the Lawson Moore and the solitary scene surrounding it. “McDonalds.”

rior to the morning of Oct. 21, 1864, Col. Sidney Jackman had a spat with Brigadier General Joseph Shelby. It is not known what triggered it.

“Sometimes men are simply in want of argument,” Calvert said.

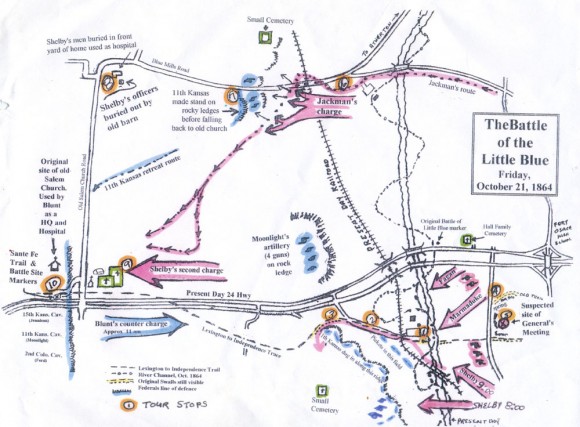

Jackman was ordered on a looping movement to test the far right Union flank along Blue Mills Road. Jackman was not flattered.

All morning Jackman could hear the engagement a mile to the south, where Shelby and generals John Marmaduke and James Fagan were fighting Col. Thomas Moonlight’s 11th Kansas Infantry, who had a small force in a field just west of the Little Blue River and the remainder on the crest of a limestone ridge overlooking the river. The Confederates, who numbered between 10,000 and 15,000 (many of whom were either unmounted or unarmed), were unaware that Brigadier General James Blunt and 1,500 men under his command had been ordered by Major General Samuel Curtis to fall back to Independence, about 8 miles west. Blunt had argued with Samuel that the position was perfect: It was high ground with a clear field of fire (there are infinitely more trees at present). Blunt knew the enemy was not far behind; two days earlier he had engaged Price at Lexington, Mo. But Curtis would not relent, knowing he would be without the Kansas militia (who would not cross the state line for Governor Thomas Carney’s fear of losing re-election) and General Alfred Pleasanton’s cavalry, who were in hot pursuit of Price’s Army from the east. Blunt was able to leave only Moonlight and his 500 troops to slow Price’s march at the Little Blue crossing.

Jackman and his men did not take their saddles until 10 a.m., two full hours after the battle began. No scout was sent ahead, assuming no threat would loom so far north.

After crossing the Little Blue, Jackman and his 80 or so men traveled up the Blue Mills Road and rounded a bend. What followed came to be known as Jackman’s Surprise. To protect his left flank, Moonlight had established some 60 men and three cannons on a ledge south of Blue Mills Road. The casualties taken by Jackman are not known; Confederate records of soldiers killed, wounded or taken prisoner were poor.

“We don’t know exactly how many men fell,” Calvert said. “But we do know there were significant losses.”

Jackman, despite the initial setback, managed to quickly gain control of his men (all of whom were mounted), sending one company on a frontal charge while the remainder hurried up a ravine to the left of the gunners, forcing them to fall back to a low ridge near the old Salem Baptist Church where reinforcements – compliments of Blunt, who learned of the need through a dispatch from Moonlight – would soon arrive.

t was Shelby’s tactical brilliance that ultimately broke Moonlight’s stronghold atop the ridge. Despite being vastly outnumbered, the 11th Kansas was able to repulse the first two attacks by the Confederates, who employed a three-pronged strategy: Shelby was positioned on the left, Marmaduke in the middle and Fagan on the right. During the third attack, Fagan, unable to cross the steep embankments, shifted left to reinforce Marmaduke, and Shelby found himself overwhelmed. Shelby had to act – and soon.

“It became one of the greatest cavalry moves of the war,” Calvert said.

Shelby did a complete shift affront, relocating his troops from the left of the attack formation, behind Marmaduke and Fagan, to the right where the undefended Lexington-Independence Road awaited. Moonlight wasn’t prepared – but it didn’t matter. He had already moved most of his men west, knowing he had been told to avoid a major conflict. When Shelby reached the outcropping, Moonlight’s troops were gone. The high ground provided Moonlight a bird’s eye view of Shelby’s troop movements and ample time to retreat what little remained of his company. If Moonlight had hesitated, Shelby could have dealt the Federals a costly blow, one that may have affected the outcome of the Battle of Westport.

ehind the ridge, Moonlight was joined by Blunt’s brigade, who mounted a prompt countercharge to stymie Fagan and Marmaduke’s advance and allow time for the arrival of Col. Charles Jennison’s 15th Kansas and Col. James Ford’s 2nd Colorado among others. With their arrival, the Federal forces now numbered 2,000 men from five regiments backed by three batteries. They formed a line greater than a mile. At approximately 11 a.m., a cannon sounded and Shelby and Jackman, nearly 1,200 calvarymen strong, surged up a hollow not far from the Lawson Moore. Jennison and Ford’s lines bowed – then they sprung back. Shelby and Jackman were familiar with Jennison and Ford; known as “Red Leggers,” Jennison and Ford were said to be guilty of so much bloodshed their socks ran red with Rebel blood.

“They were dismounted and battling hand-to-hand,” Calvert said. “There were a series of charges and countercharges, fighting rock wall to rock wall, ravine to ravine.”

Meanwhile, to the south, Blunt and Moonlight were enmeshed in a similar kind of brutality with Fagan and Marmaduke’s troops. The fighting raged four hours – with the Federals initially shoving the Confederates back a half-mile – before the Federals retreated, establishing a firing line every two miles until they reached Independence. In the engagement, the Confederates brought forward only 5,000 troops, leaving the rest in reserve and defense of Price’s famed wagon train.

It wasn’t only position that allowed the Federals to stall Price’s Army for so long. They were equipped with Spencer repeating rifles capable of 16 shots before reloading.

Casualties were rampant on both sides; Blunt reported 200 of them – and at least one prisoner taken.

“Blunt reported taking prisoner a young boy from Shelby’s brigade,” Calvert said. “My great-grandfather served in Shelby’s brigade and would have been 12 years old at that time.”

t is said that in the mid-1920s a man made haggard by old age visited the Lawson Moore Home, named for its first owner, a Kentuckian who was an affluent landowner and slaveholder.

The old man told the woman who answered the door that he had come to pay his respects to the officers buried by the barn. He said he had been wounded in a battle some 60 years earlier and was treated there. The woman told him she had wondered why her grandfather had always taken such exceptional care of a small area next to the barn.

According to Calvert, whose daughter today owns the house, eight officers are believed buried by the barn and 18 enlisted men buried beneath a row of bushes in front of the property.

The home will be within 50 yards of the proposed South Riverfront Expressway.

t At the Little Blue Parkway’s groundbreaking in September of last year, Kit Bond – a U.S. senator and longtime proponent of the parkway who secured $31 million in federal funds – told a story about a forgotten ancestor who helped pull Meriwether Lewis and William Clark up the Missouri River. He explained how, in terms of bringing progress, waterways have become roadways.

“Development is inevitable,” said Wendy Shay, historic preservation manager for the city of Independence. “The only way to defend against it is with foresight and education.”

Shay said archaeological surveys are planned for key battle sites and the city’s tourism department is at work on three illustrative markers on public property that’s easily accessible. One marker is set for Ripley Junction, where fighting began.

Still, Calvert has reason to worry. He knows how developers sometimes have a half-hearted regard for those who preceded them. If you ask, he’ll show you what he means. In the middle of the Hawthorne Apartment complex not far from the battlefield sits an old cemetery doctored by the 1960s notion of urban renewal. A square stone border reduces the original size of the cemetery by a fourth. Inside that border is a pool of concrete, tombstones impressed into it like a kid’s game of tic-tac-toe.

I hate that we lose historical sites and buildings to progress. There is plenty of room for expansion in other areas. My heart breaks

I know we have to make advancements, but I think we have so much ground now holding empty buildings, that could be housing, we have many decent road taking us from 40 hiway to 24 hiway. The more of our History that we cover up or ignor, the more we allow our America to be replaced by a country I don’t even recognize anymore, because it is filled with the history or people who have BROUGHT their own history here and expect us to embrace it, and our own is being stripped away to make room for them……